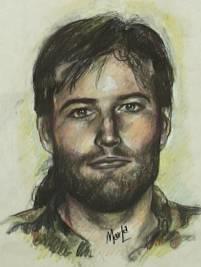

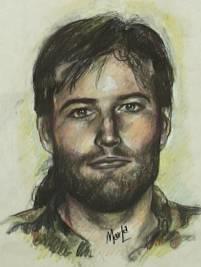

Forensic Artist Marla Lawson

Like most artists, Marla Lawson surrounds herself with the tools of the trade - clays, paints and brushes. But Marla is not your typical artist, and her works can't be found in any art gallery. She is a forensic artist with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI), and her sketches and reconstructions are used to nab suspects and identify unknown remains.

The GBI enlisted Lawson's talents in 1997, but the self-taught artist's career began decades before. For 15 years, she rendered composite drawings of suspects based on descriptions by their victims for the Atlanta Police Department. In 1991 though, she decided to call it quits.

That hiatus was brief. A robbery at a sandwich shop where she worked forced her to break out the pad and pencil once again.

"I went home that night, and sketched the robbery suspect and turned it over to the local authorities," said Lawson. "I realized that the private sector was no place for me. I needed to be doing something to help others."

And help is what Lawson did. The suspect, who robbed the eatery, also hit a gift shop down the road. Based on her drawing, the robber was apprehended.

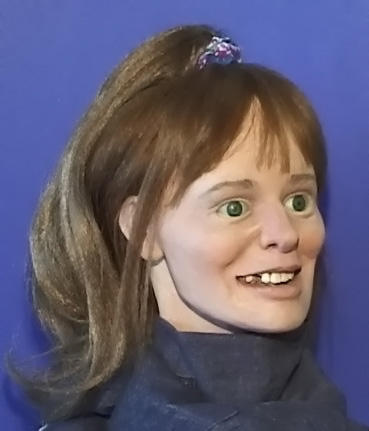

In 2000, Lawson developed a new art. With the use of clay, she sculpts busts from skulls provided by law enforcement agencies and medical examiners offices. She performed about 45 reconstructions during the year for agencies across the state, giving unknown remains faces and a chance at being identified.

The process begins with a review of case information supplied by the requesting agency. Where the skeleton was discovered, what type of clothing was worn, what items were found in his or her possession and hair left behind at the scene all provide Lawson with valuable insight into the person-in-question's physical appearance. The dimensions of the skull also are telling, but much of the reconstruction comes from Lawson's skill and imagination.

"It is not an exact science. A lot of what I do is guesswork," she said. "There is no real way of knowing, but I try to follow my instincts and give each reconstruction its own individual look."

Lawson's efforts are paying off, and her works have been instrumental in identifying remains.

"This is someone's child, grandchild, brother or sister, she says, smoothing the clay on her latest reconstruction. "I think what if this was my child. I would want to have some closure."

FORENSIC RECONSTRUCTIONS

Step 1

Lawson begins the three-dimensional reconstruction process with a fact-finding mission. Case information supplied by the requesting agency is reviewed to learn more about the individual in question. Where the remains were discovered, what type of clothing was worn, and personal effects found at the scene all provide Lawson with valuable insight into physical appearance. The skull, itself, reveals approximate age, sex, build and race.

For decades, forensic artists and pathologists have been researching and developing ways to make reconstructions based on skulls more accurate. Lawson defers to that expertise as she begins work on every sculpture. After mounting the skull onto a metal pole, creating a makeshift neck, she uses small, depth markers, numbered and varied in length, to define facial features. Anthropologists and pathologists developed the method of using the markers by measuring the thickness of facial tissue on male and female cadavers representing diverse ages and races. The compiled data provides forensic artists like Lawson with a guide in determining the contour of the face; the shape, thickness and length of the nose; the width of the mouth; and the placement of the eyes.

Step 3

Once the markers have been glued onto the skull, Lawson uses clay to fill in the various cavities and places artificial eyes in the orbital sockets. Selecting eye color is a guess, so Lawson relies on the clues that the skull provides. Certain eye colors are dominant among races. For example, if the bone structure indicates that the skull belongs to an African American, then brown eyes would be used. If the skull is believed to belong to a Caucasian, then making a selection is more difficult. She often goes with brown because it is a common eye color.

Step 4

Now the sculpting begins. The markers and the contours of the skull are used as guides as the clay is systematically added. The mouth and the nose are formed based on the width and length of the skull's landmarks. Here, Lawson uses the information she has learned about the subject based on the personal effects found at the scene. Teeth also are vital to the reconstruction process. If there are teeth remaining in the skull, Lawson often sculpts the bust with a smile.

Step 5

Next, Lawson makes the bust more life-like by adding hair and giving the face color. Sometime hair found with the remains indicates what color to use, but like the eyes, hair color, length and style often is left to the artist's discretion. Once a wig is in place, Lawson paints the sculpture in flesh tones and blushes - a process that many forensic artists skip. Lawson, however, likes to make the sculptures as realistic as possible in the hope of making the reconstruction more identifiable.

Step 6

With the sculpture complete, Lawson turns over the bust to the agency that requested the reconstruction. It is then photographed, placed on flyers and distributed to the public and the media.